Meet the Legend: Jim Fitzpatrick

We recently had the pleasure of chatting with legendary Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick at his home studio in County Dublin, close to Howth. An incredible story this man has to tell, with an energy & creativity that still burns brightly. We discussed his recent work on the logo for young Belfast band, Dea Matrona, how he met Che Guevara which led to him produce one of the most iconic posters in modern history, his friendship with Phil Lynott from Thin Lizzy, memories of meeting Belfast guitar legend Gary Moore, working with Downpatrick rock trio Ash, his orange & green heritage and his hopes for his paintings someday being used in Belfast to help build respect & understanding across the city.

(This is an extract from the full article in YEO4. Go grab it if you fancy.)

Lee: How have you

maintained your enduring passion for art?

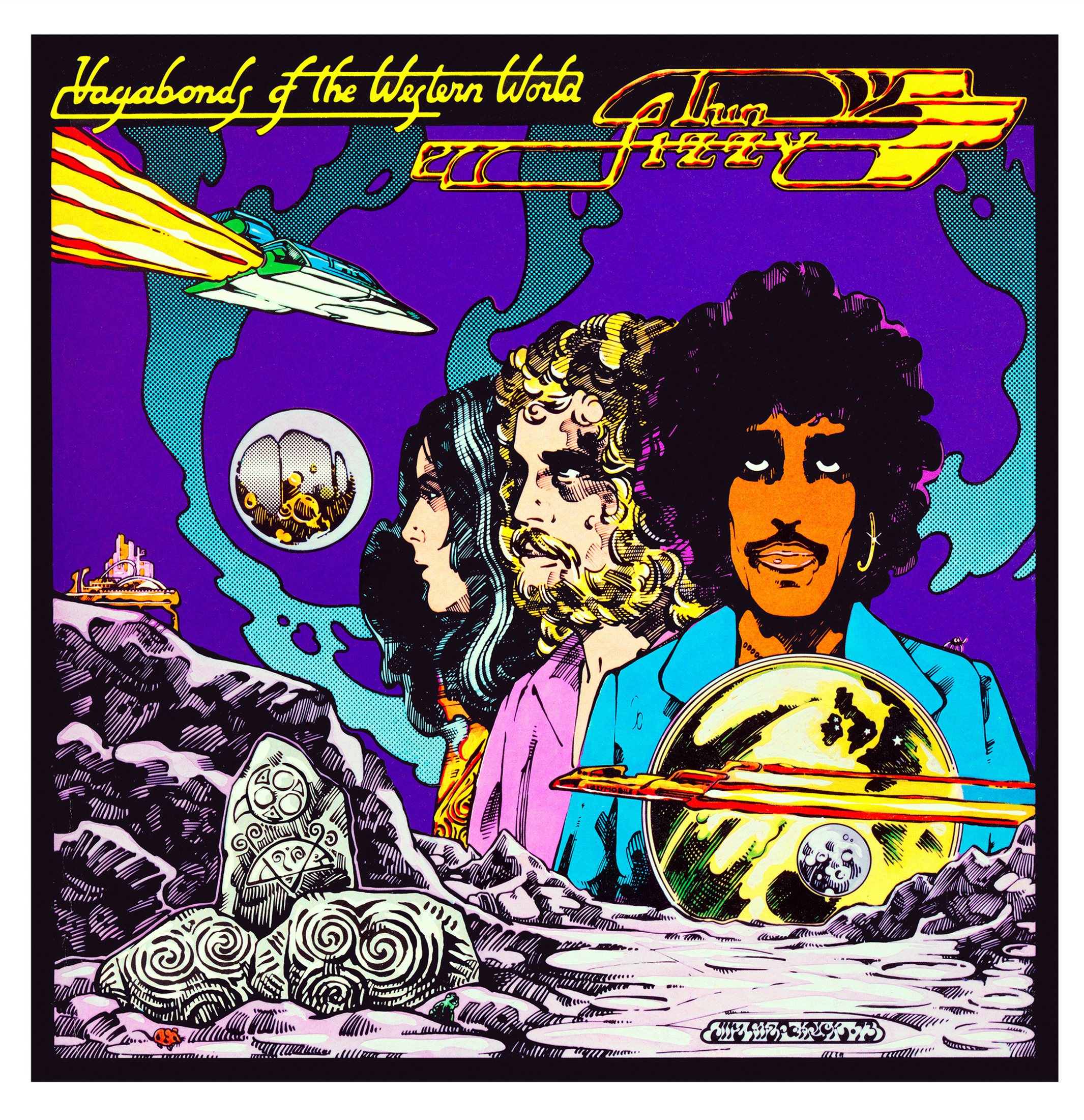

Jim: It never subsides, it just fuckin’ kills me at this point. I’m at the point in my life where I’m taking stock of everything I’ve done. My son runs my blog and he gets me to write a story of each of the ‘Lizzy’ works for instance, and we’re gonna apply that to everything. And I thought, Jesus Christ, I’d need another lifetime to do that. The Lizzy stuff I can do easily, but the Celtic (art) stuff would be a bit of a fuckin’ nightmare cause there’s so much of it. But I have done hundreds of thousands of other works. So I spent yesterday in the attic digging out all the Lizzy files. They are fairly organised, now all over the floor here. I’ve come across three original albums, ‘Vagabonds of the Western World’, and three ‘Johnny the Fox’ pieces I didn’t even know I had. I have a signed ‘Jailbreak’ with Phil Lynott and Thin Lizzy. It’s great stuff, but you have to catalogue it all, cause they want me to archive it. My archiver has catalogued all of Martin McDonagh’s scripts, who directed ‘Three Billboards’, and they want to do the same with all of my stuff for an American University.

I want to archive it anyway because it’s just a mess. So that’s what I’ve been doing instead of working, which is what I want to do. My son lives in LA, my daughter is in Milan and we all work together on all this stuff. But the bastard that has to do the most work is me (laughing). I was very smart. When I was doing my Celtic work especially, I photographed everything in advance, all the line work before I painted it, just big photocopies. My daughter is doing colourised versions. I am working with two of the top colourists in America, Eric Hope and Lovern Kindzierski, who actually invented computer colouring for comics.They are working with me on a series of stuff as well. I’ve so many old drawings. I did a series of drawings of ‘Nuada of the The Silver Arm’ in black & white, very detailed, but I never did anything with them. But now Lovern Kindzierski has worked on a few of them and he has just transformed them.

Lee: You have appeal that stretches across generations. For example, you recently designed the artwork for Belfast rock band Dea Matrona. How did that one come about?

Jim: Ah indeed, tell them to give me a buzz, as I have an idea for them. I did a beautiful logo for them, but I don’t think they realised it would be so easy to turn that into a hippie logo using patterns. When I was doing the logo, I do everything in black & white, but that doesn’t mean it’s gonna stay that way. I love the way they dress, total hippy shit! They could be anything they want.

![]()

I am an honorary Director of a thing called ‘HERstory’ - rewriting history essentially and honouring all of the women that have been overlooked, including a Northerner - Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who discovered pulsars, which led to the discovery of Black Holes, at the age of 29 in 1974, I believe. In their wisdom, the Nobel Science Prize was awarded to that discovery, but they gave it to the men, her supervisors, not her. I have since met her and painted her for an exhibition at DCU. So, I just like the idea of a girl rock band. I’d love to see an Irish female rock band do well. I couldn’t care if they were black, white, Catholic or Protestant. Dea Matrona have the talent to do it. They are fuckin’ great players, better than Thin Lizzy were at that time in their career (laughing).

Lee: You met Che Guevara briefly in County Clare in 1961. Can you recall your memories of that meeting?

Jim: I was working as a barman at the Marine Hotel in Clare with my friend Gilbert Brosnan. We were only 16 at the time, earning money for the summer holidays. We were sent down to Kilkee by the Franciscans, to try and earn some money for a pilgrimage to Rome. They wouldn’t allow the rich kids to pay, everyone had to earn the money themselves. Literally, my mother was spending every penny she had putting me through college. One day on a Sunday after mass, I’m standing there at the bar, talking to a regular called Sam, who everybody down there remembers still, who just lived in the bar, and in walked Che Guevara. Being a political animal, educated by Franciscans, who had a huge mission in Latin America and knew the entire story of the Irish diaspora, they greeted him and he was mightily impressed. A charming man, and he turned to me and said, in the course of the conversation, “Well I’m Irish, you know?” That bit got me, I’ve never forgotten that.

Aleida Guevara’s daughter denies that, but I found an old interview with Maureen O’Hara who was a mutual friend of some of ours, Morgan Llywelyn, the writer. O’Hara was doing a movie for John Houston in Havana, and in the hotel where she had her breakfast, Che Guevara came in every morning for a coffee, and would always join her. In the end she said to him, “How do you know so much about the Irish War of Independence?” And he said, “because I’m Irish, and I study it, and I applied those methods in the Sierra Madre mountains.” That’s on the record.

His brother Juan Martin, who’s in his 80s, is being filmed by an Irish filmographer, and two years ago they published a piece on the Internet of Juan Martin being interviewed. I remember him saying that the Guevara family denied the Irish connection for emotional reasons. I don’t think they liked Guevara Lynch, the Da at all, and I don’t think he liked them much. There’s kind of ‘white-laced’ Cubans and ‘shanty’ Cubans, same as there is ‘white-laced’ Irish and ‘shanty’ Irish in Argentina, and never the twain shall meet. Even a revolution can’t fix that. So Juan Martin has come out and said that Guevara Lynch, the father, was immensely proud of the Irish connection, and the Irish & Basque connection, because he was both. But he always said that he much preferred the Irish, because they were more fun and the Basque were too bloody serious (laughing). Sex, drugs and rock n’roll essentially. I think that’s why (the family) don't like the Irish connection, but that’s just a guess on my part.

![]()

Lee: The photo by Korda was taken in 1960, but not published until 1967. What were your thoughts when you first saw this iconic photograph and why did you decide to put your own artistic spin on it?

Jim: Well, I’d met Guevara and when he went to Bolivia, I was mightily impressed. I worked in advertising and we used to subscribe to Stern Magazine and a lot of international magazines because that way we could keep up with good layout & good design. Stern Magazine published on their cover a photograph of Guevara taken by himself as ‘Carlos’ (to enter Bolivia), with the hair slicked back, grey, smoking a cigar. I think he shaved the top of his head to look totally bald, and was in a suit. He was a very good photographer himself remember, so he took a picture and Stern Magazine put it on their cover. On the inside of the magazine there was a picture of him riding a mule, dressed in combats. He had gone there to lead a revolution and I was like, ‘Wow!’. It was big news and at that time I was working for ‘Scene’ Magazine doing a series called ‘A Voice In Our Time.’ For the April 1967 edition, I did a full-page cartoon as part of this series. For example, I had done the Reverend Ian Paisley with a big Union Jack behind him denouncing all kinds of shite; Lyndon Johnson and Howard Wilson as his poodle during the Vietnam War. The third one was Che Guevara with the call to arms with Che’s slogan of ‘the rattle of a machine gun’ and so on. And the editor being a very nice Englishman was having none of it and he wouldn’t publish it. So I turned it into my poster from a black & white drawing when he was murdered (in October 1967). That was the first Che Guevara poster anywhere in the world as far as I could see, and that was verified by the 2006 travelling Korda exhibition. Then I was commissioned for an exhibition in May 1968 in London, entitled ‘Vive Che.’ That’s what I did the red and black one for. But the problem was, I also did a full oil painting & the graphic I did for the magazine, and they were all shipped over to England and I never saw them again.

After that, I bought a Nikon camera and I photographed fuckin’ everything I did. It taught me a lesson. The Che Guevara artwork was easy because I had huge paper negatives that are still at home here and I have in the attic. At the last moment, I changed my mind and simply sent them a copy (of the red and black version) of it by post. That became the red and back poster that you know today. And that was ripped off almost immediately. I went over to London three months later, as suddenly, all the phone calls from the exhibition organiser, Peter Mayer had stopped and I was absolutely distraught as I wanted that work back. When I went to London, it was in every poster shop. I remember going into Felix Dennis in OZ (counter-culture magazine), and trying to say to him, “Look, I own the red & black one, we should do it to stop all this.” But he was already doing the Korda photograph which had a sign on it that said ‘copyright Feltrinelli.’ I thought that Feltrinelli was the photographer, the Italian revolutionary who ripped it off, and according to Korda made millions, but Korda never saw any of it. He got the photograph of it from Korda when he was with Jean-Paul Sarte, the philosopher. The two of them went to Korda’s studio and he gave them a print. Feltrinelli promptly went to Italy and ran it off in the millions, and made money from it. He was super-rich himself anyway. It was only years later that Korda realised that I’d actually made his image quite famous (chuckling). I explained to him, via a contact from RTE, that it was an Irish fella that had done the red & black one. That was the first he had heard of it (laughing).

Interestingly, in 2008, Jim announced that he would be signing over the copyright of his Che image to the William Soler Pediatric Cardiology Hospital in Havana, Cuba. Jim was quoted at the time saying, "Cuba trains doctors and then sends them around the world. I want their medical system to benefit." Additionally, he publicised his desire to gift the original artwork to the Cuban people via the archive run by Guevara's widow, Aleida March.

![]()

Lee: Thin Lizzy's 'Vagabonds' album cover is almost 50 years old. It was the first album cover that you designed for the band. Can you tell me some more about that first meeting with Phil Lynott and how the conversation ended up you working as their main illustrator?

Jim: I was doing a lot of work in Dublin at the time, like doing poetry covers for writers and groups. A guy called Eamon Carr, a writer-journalist, who is still around, had two of the poster poems that I did, one of them with his poem on it, pinned to his wall. Philip came in, saw them and said, “Wow, brilliant stuff, West Coast stuff, I love that kind of psychedelic work.” And Eamon said, “no, that’s a local guy, Jim Fitzpatrick.” We had met briefly in Roy Esmonde’s studio when we had our portraits taken at the same time in 1967. We‘d nodded on the stairs, we knew each other to see. When Thin Lizzy was formed, one of Philip’s best friends was an artist called Tim Booth, who was also a friend of mine. Dublin is a very small place. Tim was to do all the Thin Lizzy album covers, and he had designed the first kind of catalogue style Lizzy logo, the one at the top of the ‘Vagabonds’ album, which I made broader. He was in a band called Dr Strangely Strange. You couldn’t make this up. They were under Chris Blackwell of Island Records, one of the first signings he had ever made. And guess who did their first album cover? - Roger Dean, another friend of mine. So, Tim was under contract with Island, Lizzy was with Decca, so he wasn’t allowed to work for them.

So Frank Murray, who I played football with and was Philip’s best friend when they lived together in London decided he was going to introduce Philip to me. Philip hadn’t made the connection between the posters on Eamon Carr’s wall and my work. It took him around ten minutes to kop on, this was the guy who’s work he was admiring. So from that point on we hit it off like a house on fire. That was about 1971, because in 1972 I was over staying with him in London.

Jim: It never subsides, it just fuckin’ kills me at this point. I’m at the point in my life where I’m taking stock of everything I’ve done. My son runs my blog and he gets me to write a story of each of the ‘Lizzy’ works for instance, and we’re gonna apply that to everything. And I thought, Jesus Christ, I’d need another lifetime to do that. The Lizzy stuff I can do easily, but the Celtic (art) stuff would be a bit of a fuckin’ nightmare cause there’s so much of it. But I have done hundreds of thousands of other works. So I spent yesterday in the attic digging out all the Lizzy files. They are fairly organised, now all over the floor here. I’ve come across three original albums, ‘Vagabonds of the Western World’, and three ‘Johnny the Fox’ pieces I didn’t even know I had. I have a signed ‘Jailbreak’ with Phil Lynott and Thin Lizzy. It’s great stuff, but you have to catalogue it all, cause they want me to archive it. My archiver has catalogued all of Martin McDonagh’s scripts, who directed ‘Three Billboards’, and they want to do the same with all of my stuff for an American University.

I want to archive it anyway because it’s just a mess. So that’s what I’ve been doing instead of working, which is what I want to do. My son lives in LA, my daughter is in Milan and we all work together on all this stuff. But the bastard that has to do the most work is me (laughing). I was very smart. When I was doing my Celtic work especially, I photographed everything in advance, all the line work before I painted it, just big photocopies. My daughter is doing colourised versions. I am working with two of the top colourists in America, Eric Hope and Lovern Kindzierski, who actually invented computer colouring for comics.They are working with me on a series of stuff as well. I’ve so many old drawings. I did a series of drawings of ‘Nuada of the The Silver Arm’ in black & white, very detailed, but I never did anything with them. But now Lovern Kindzierski has worked on a few of them and he has just transformed them.

Lee: You have appeal that stretches across generations. For example, you recently designed the artwork for Belfast rock band Dea Matrona. How did that one come about?

Jim: Ah indeed, tell them to give me a buzz, as I have an idea for them. I did a beautiful logo for them, but I don’t think they realised it would be so easy to turn that into a hippie logo using patterns. When I was doing the logo, I do everything in black & white, but that doesn’t mean it’s gonna stay that way. I love the way they dress, total hippy shit! They could be anything they want.

I am an honorary Director of a thing called ‘HERstory’ - rewriting history essentially and honouring all of the women that have been overlooked, including a Northerner - Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who discovered pulsars, which led to the discovery of Black Holes, at the age of 29 in 1974, I believe. In their wisdom, the Nobel Science Prize was awarded to that discovery, but they gave it to the men, her supervisors, not her. I have since met her and painted her for an exhibition at DCU. So, I just like the idea of a girl rock band. I’d love to see an Irish female rock band do well. I couldn’t care if they were black, white, Catholic or Protestant. Dea Matrona have the talent to do it. They are fuckin’ great players, better than Thin Lizzy were at that time in their career (laughing).

Lee: You met Che Guevara briefly in County Clare in 1961. Can you recall your memories of that meeting?

Jim: I was working as a barman at the Marine Hotel in Clare with my friend Gilbert Brosnan. We were only 16 at the time, earning money for the summer holidays. We were sent down to Kilkee by the Franciscans, to try and earn some money for a pilgrimage to Rome. They wouldn’t allow the rich kids to pay, everyone had to earn the money themselves. Literally, my mother was spending every penny she had putting me through college. One day on a Sunday after mass, I’m standing there at the bar, talking to a regular called Sam, who everybody down there remembers still, who just lived in the bar, and in walked Che Guevara. Being a political animal, educated by Franciscans, who had a huge mission in Latin America and knew the entire story of the Irish diaspora, they greeted him and he was mightily impressed. A charming man, and he turned to me and said, in the course of the conversation, “Well I’m Irish, you know?” That bit got me, I’ve never forgotten that.

Aleida Guevara’s daughter denies that, but I found an old interview with Maureen O’Hara who was a mutual friend of some of ours, Morgan Llywelyn, the writer. O’Hara was doing a movie for John Houston in Havana, and in the hotel where she had her breakfast, Che Guevara came in every morning for a coffee, and would always join her. In the end she said to him, “How do you know so much about the Irish War of Independence?” And he said, “because I’m Irish, and I study it, and I applied those methods in the Sierra Madre mountains.” That’s on the record.

His brother Juan Martin, who’s in his 80s, is being filmed by an Irish filmographer, and two years ago they published a piece on the Internet of Juan Martin being interviewed. I remember him saying that the Guevara family denied the Irish connection for emotional reasons. I don’t think they liked Guevara Lynch, the Da at all, and I don’t think he liked them much. There’s kind of ‘white-laced’ Cubans and ‘shanty’ Cubans, same as there is ‘white-laced’ Irish and ‘shanty’ Irish in Argentina, and never the twain shall meet. Even a revolution can’t fix that. So Juan Martin has come out and said that Guevara Lynch, the father, was immensely proud of the Irish connection, and the Irish & Basque connection, because he was both. But he always said that he much preferred the Irish, because they were more fun and the Basque were too bloody serious (laughing). Sex, drugs and rock n’roll essentially. I think that’s why (the family) don't like the Irish connection, but that’s just a guess on my part.

Lee: The photo by Korda was taken in 1960, but not published until 1967. What were your thoughts when you first saw this iconic photograph and why did you decide to put your own artistic spin on it?

Jim: Well, I’d met Guevara and when he went to Bolivia, I was mightily impressed. I worked in advertising and we used to subscribe to Stern Magazine and a lot of international magazines because that way we could keep up with good layout & good design. Stern Magazine published on their cover a photograph of Guevara taken by himself as ‘Carlos’ (to enter Bolivia), with the hair slicked back, grey, smoking a cigar. I think he shaved the top of his head to look totally bald, and was in a suit. He was a very good photographer himself remember, so he took a picture and Stern Magazine put it on their cover. On the inside of the magazine there was a picture of him riding a mule, dressed in combats. He had gone there to lead a revolution and I was like, ‘Wow!’. It was big news and at that time I was working for ‘Scene’ Magazine doing a series called ‘A Voice In Our Time.’ For the April 1967 edition, I did a full-page cartoon as part of this series. For example, I had done the Reverend Ian Paisley with a big Union Jack behind him denouncing all kinds of shite; Lyndon Johnson and Howard Wilson as his poodle during the Vietnam War. The third one was Che Guevara with the call to arms with Che’s slogan of ‘the rattle of a machine gun’ and so on. And the editor being a very nice Englishman was having none of it and he wouldn’t publish it. So I turned it into my poster from a black & white drawing when he was murdered (in October 1967). That was the first Che Guevara poster anywhere in the world as far as I could see, and that was verified by the 2006 travelling Korda exhibition. Then I was commissioned for an exhibition in May 1968 in London, entitled ‘Vive Che.’ That’s what I did the red and black one for. But the problem was, I also did a full oil painting & the graphic I did for the magazine, and they were all shipped over to England and I never saw them again.

After that, I bought a Nikon camera and I photographed fuckin’ everything I did. It taught me a lesson. The Che Guevara artwork was easy because I had huge paper negatives that are still at home here and I have in the attic. At the last moment, I changed my mind and simply sent them a copy (of the red and black version) of it by post. That became the red and back poster that you know today. And that was ripped off almost immediately. I went over to London three months later, as suddenly, all the phone calls from the exhibition organiser, Peter Mayer had stopped and I was absolutely distraught as I wanted that work back. When I went to London, it was in every poster shop. I remember going into Felix Dennis in OZ (counter-culture magazine), and trying to say to him, “Look, I own the red & black one, we should do it to stop all this.” But he was already doing the Korda photograph which had a sign on it that said ‘copyright Feltrinelli.’ I thought that Feltrinelli was the photographer, the Italian revolutionary who ripped it off, and according to Korda made millions, but Korda never saw any of it. He got the photograph of it from Korda when he was with Jean-Paul Sarte, the philosopher. The two of them went to Korda’s studio and he gave them a print. Feltrinelli promptly went to Italy and ran it off in the millions, and made money from it. He was super-rich himself anyway. It was only years later that Korda realised that I’d actually made his image quite famous (chuckling). I explained to him, via a contact from RTE, that it was an Irish fella that had done the red & black one. That was the first he had heard of it (laughing).

Interestingly, in 2008, Jim announced that he would be signing over the copyright of his Che image to the William Soler Pediatric Cardiology Hospital in Havana, Cuba. Jim was quoted at the time saying, "Cuba trains doctors and then sends them around the world. I want their medical system to benefit." Additionally, he publicised his desire to gift the original artwork to the Cuban people via the archive run by Guevara's widow, Aleida March.

Lee: Thin Lizzy's 'Vagabonds' album cover is almost 50 years old. It was the first album cover that you designed for the band. Can you tell me some more about that first meeting with Phil Lynott and how the conversation ended up you working as their main illustrator?

Jim: I was doing a lot of work in Dublin at the time, like doing poetry covers for writers and groups. A guy called Eamon Carr, a writer-journalist, who is still around, had two of the poster poems that I did, one of them with his poem on it, pinned to his wall. Philip came in, saw them and said, “Wow, brilliant stuff, West Coast stuff, I love that kind of psychedelic work.” And Eamon said, “no, that’s a local guy, Jim Fitzpatrick.” We had met briefly in Roy Esmonde’s studio when we had our portraits taken at the same time in 1967. We‘d nodded on the stairs, we knew each other to see. When Thin Lizzy was formed, one of Philip’s best friends was an artist called Tim Booth, who was also a friend of mine. Dublin is a very small place. Tim was to do all the Thin Lizzy album covers, and he had designed the first kind of catalogue style Lizzy logo, the one at the top of the ‘Vagabonds’ album, which I made broader. He was in a band called Dr Strangely Strange. You couldn’t make this up. They were under Chris Blackwell of Island Records, one of the first signings he had ever made. And guess who did their first album cover? - Roger Dean, another friend of mine. So, Tim was under contract with Island, Lizzy was with Decca, so he wasn’t allowed to work for them.

So Frank Murray, who I played football with and was Philip’s best friend when they lived together in London decided he was going to introduce Philip to me. Philip hadn’t made the connection between the posters on Eamon Carr’s wall and my work. It took him around ten minutes to kop on, this was the guy who’s work he was admiring. So from that point on we hit it off like a house on fire. That was about 1971, because in 1972 I was over staying with him in London.